With Anima Mundi, Vril departs from his Berghain roots and delivers an introspective exploration of his eternal soul.

If I’m allowed to have favorites, I would claim Vril, the German DJ and Resident Advisor Lieutenant, as mine among his genre, which shouldn’t mean anything to the longtime techno connoisseur (who should probably find themselves skipping this review and moving on,) but does lend me to evangelize to those who’ve been deprived of positive exposure to the culture. Most any electronic music can be transportive and my own affection for it can no doubt be attributed at least in part to my near-total isolation from its community. I have never been to a proper club (the only offering in the setting of my young adulthood has never aspired beyond squishy DJs who are now somehow 100% content describing their scene as “EDM,") and I’ve only had a few friends with whom I could share significant interest, though their knowledge was extraordinarily extensive. It takes incisive wisdom to cut through “Techno” as the misnomer it has become in today’s America - a subject deserving its own, more deliberate discussion - but for the moment, let’s consider a single record which manages to exemplify the potential of this historically-niche medium.

For years, I’ve been one hundred percent sure that “Vril” is a proper noun, but I could very well have gone on living the rest of my life never deciding between whom or where. Up until Anima Mundi’s release on October 15th (technically it was released last year, but exclusively on cassette,) his catalog was consistently Vril - on-brand, you might say - though in the most respectable sense for a dance DJ, I’d imagine. I can’t quite recall the moment of discovery, but I do know that the dozen or so of his live mixes available on Mixcloud caught my attention immediately afterward. There’s something magic in the layers that grabs an unnamed rhythmic organ of mine in a way that cannot be expressed in written form without experience I do not have. What I can provide is the most comprehensively concise example I can find: a live set from the infamous Berghain in 2014.

Regardless if I’m writing, walking(?,) or chasing gravel apexes, these mixes always kick me into another plane, where the panning high hat halos are biased astray by a fraction of a degree, delaying a false local disorientation akin to the sound of a dozen choreographed kindergarten tap dancers' feet next to one’s head, mildly duration-compressed. Techno as a whole has become quite comfortable with the practice of orbiting high frequency percussion in elongated ellipses around the stereo picture, which I’ve adored and defended since day 1. My hypotheses: it’s actually a cheap shot for the psyche’s potential desire for justification of their club experience as something transcendent. It’s a pretty easy cheat to keep the listener’s immediate environment feeling expansive, reflective, and therefore meaningful. I, myself am probably drawn to its threatening aura of imminent contiguous industrial emergency, but again, I’ve never been to Berghain, London, or Stockholm, nor has my adult nightime recreation ever found me in any venue to which one could attribute the term “club” without immediately ``chuckling. This music has not traditionally found its place among lives like mine, and nobody even seems interested in figuring out why.

It seems like there was a big thirst for these kinds of intentions. But the more attention we get, the harder it gets to keep those intentions up and not get washed away by the perception of others. Who are maybe searching for something that sometimes seems impossible to deliver.

For the hell of it, let’s begin by removing one of techno’s most notoriously-defining categorical descriptors: “dance music.” I’ve done this personally - aside from moderate head-bobbing - but I’ve already got a bad habit of miscontextuallizing music, so let’s focus on our hypothetical technovirgin, Gavin, who thought Bassnecter was amazing in 8th grade, can “sometimes fuck with” run-of-the-mill dubstep, plays college football, and is generally more serious about schoolwork than the trashy campus bars he visits every other weekend out of a vague desire for female attention. Let’s have faith in Gavin and assume that he doesn’t need perspective-altering narcotics to be introspective, but we’ll wait until he’s alone in his shitty dorm in the early morning hours, typing out an American History essay on his MacBook. He’s in his bed, earbud-equipped noggin propped uncomfortably against the wall, machine resting on his diaphragm. It’s streaming fucking Aphex Twin from some stranger’s Spotify playlist, which we’ve hacked. Just after “Windowlicker"’s last, foul moan, we’ll covertly begin this involuntary acquaintance with “Manium"’s simple fade-in.

It’s sincerely serious, contemplative, science fiction-esque, but certainly not even as manic as the tasteless breast-obsessed number one hit he’s just heard. In fact, the contrast is so sharp that his attention is agitated away from his sentence, and he looks off the screen across the room to the door’s electronic knob. According to whomever wrote Delsin’s description of the album, Gavin has just unwittingly set upon “a deep excursion for mind and body” - a phrase which would no doubt make him a bit uncomfortable, yet here, alone, or perhaps in the back seat of the right friend’s car on a long drive, its acute caution compels his mind to consider the heaviest possible question of the moment: something about finals, I would guess. His brow slowly scrunches in the Word document’s soft white glow. The unchanging dissonance from the background synth’s single chord grows louder and louder, gradually, before dropping briskly, allowing for the similar successive fade-in of “Statera Rerum.”

Layer number one is surely a four-second sample of a dot matrix printer’s operation, slowed and pitched-down thirty or so percent - reminiscent of the phenomena to which shopping cart castors are commonly subject: a certain speed’s vibration triggers a sort of resonant buzzing freakout. Vril’s simplistic construction continues with another mechanical layer, then panned pulsar synths which ebb and recede in lazier loops across the spectrum. By now, Gavin is on his way back to reality and has finally begun alt-tabbing by the last few seconds of track 2. Just as he finds and restores his Spotify window, it has ended, and the album’s title track begins. His investigation is stymied for a beat by the identical track and album metadata, but he’s still curious enough to search the album out after figuring it out. Since this is a hypothetical world, let’s make it just a bit better and assume Anima Mundi’s Bandcamp page is the first result returned by Gavin’s search engine with its brief, but gorgeous motion graphic promo video, which he allows to play parallel with track 3 on Spotify since it’s less than 30 seconds.

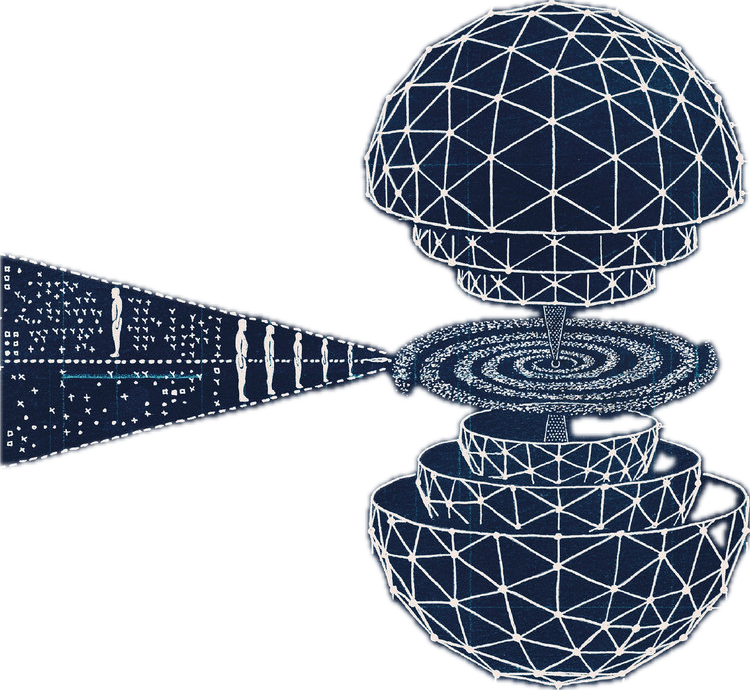

The resulting cacophony is unlike anything he has ever heard, and - probably in reaction to his essay topic’s inability to stimulate him whatsoever - its somewhat extended battle cry elicits sufficient intrigue to keep his attention from straying further. It’s a lucky thing, too, because the rework of “Riese” (literally “giant") is up next, and it’s the most profound and unexpected groove on the whole record. It’s rhythmless, reflective, and very cinematic in a similar (but far far superior) doctrine to Hans Zimmer’s use of simplistic, swelling harmonious chords to blast audiences' emotional intelligence to smithereens behind films like Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor and J.J. Abrams' Star Trek. According to Inverted Audio’s review, its notes “lose their dissociative feeling for something a bit more intimate and in turn gain even more emotional power over the listener.” Essentially, it’s real gorgeous, though Gavin’s not quite in a vulnerable enough state to be moved to tears. So far, Anima Mundi has been almost entirely separate from “techno” as it is commonly defined, but it’s clear to even the most casual fan of the scene that it’s definitely an addendum, not abandonment. I could be wrong, but as a fan of Vril’s, I’ve found the four tracks Gavin’s heard up to this point feel almost like the endnotes to the more brisk, purposeful melodic and rhythmic identities formed in Portal, his first album, along his years of live club arrangements. If I were to be a bit bold, I’d surmise that Vril could consider Anima Muni an artistic declaration: just so you know, I am a lot more than just the guy behind the booth - I am a “world soul."

I’m afraid it would be dishonest of me to extract a happy ending from my derriere for this hypothetical of ours because of a single word in track 5’s title with truly awesome power among the Youth of Today: anime. In Spring 2017, I recorded Futureland’s most entertaining episode with my good friend Tevin, who happens to be a beautiful bridge between fraternity culture and Japanese Animated Video Content, yet lacks faith in the former’s chances of progressing much at all, going forward. Gavin has probably been exposed to anime once or twice, but for him, it’s unlikely to ever become anything but a punchline. “Infinitum Eternis Anime” means (roughly) “infinite eternal soul,” and it’s the record’s first amalgam of recognizably techno elements (for which I do not know any of the industry/jargon terms, so do forgive my lack of detail.) It’s a shame Gavin won’t give it a chance because it’d likely serve as an effective gateway drug for a more sophisticated nightlife, but I’m sure you were getting awfully tired of him, anyway. To cite Inverted Audio’s Will Long once more:

Each one of the tracks from the ‘Haus’ EP works even better in the context of the full record. “Haus” gets an even smoother, more melodic rework; “Riese” is also more melodic in construction with the beat stripped away in favour of more reverb and sustained notes. They lose their dissociative feeling for something a bit more intimate and in turn gain even more emotional power over the listener.

Though his comparison of Anima Mundi to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was quite crude, I can obviously concur with some of his other language, like “future classic,” and “buy on sight.” As much as I’d like to further indulge my own analysis of the rest of the 80 minute work’s tracks, one-by-one, let me just conclude by doting on my personal favorite track, “Sine Fine.” Without resorting to the word “ambiance,” I can’t say much, but - above all - it’s Track 10 that takes me to The Vril Place in which I have always felt so intrigued and comfortable. Buy Anima Mundi right fucking now.